On Joseph Roth, the edge, and the end

The complicated life of European literature's master of melancholy

In an angry letter to his friend and benefactor (protector?) Stefan Zweig, written in 1936, Joseph Roth described himself as “a believing eastern Jew from Radziwillow”.

As with seemingly every thought or assertion Roth committed to the page, this statement is fraught with ambiguity. He was certainly Eastern, but not from the Polish town of Radzillow, but from Brody, in present-day Ukraine, And while his background was certainly Jewish, he was drawn to and identified often as Catholic.

Roth is the subject of Kieron Pim’s biography Endless Flight, bizarrely the first full account of the Radetzky March author’s life in English, (a mention should be made here of the late Dennis Marks’ Wandering Jew - The Search For Joseph Roth an enthralling monograph-cum-travelogue that attempts to follow Roth and his writing across the old empire of the Habsburgs).

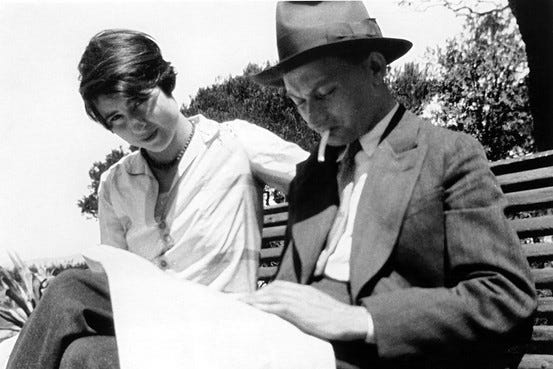

Joseph Roth and Friedl Reichler

By Pim’s illuminating and exhaustive account, Roth was a child of what is now called the liminal space: an Eastern Jew brought who didn’t speak the Yiddish of the shtetl, but the high German of Vienna. A boy who, having lost a young father to madness, was simultaneously expected to be the man of the house but also endlessly cosseted by a mother who would walk him to school every day, even in his teens, and discouraged friends and socialising.

Roth’s novels and journalism are dominated by his grief at the lost world of the Austro Hungarian empire - for him a bastion of multiculturalism. But there is so much more for the reader than crass nostalgia. Roth understood the dangers of sentimentality - a masquerade that replaces real emotion, thought, and above all conscience, an essential concept that runs through all his writings.

JM Coetzee suggested that “Roth is not a modernist. Part of the reason is ideological, part temperamental, part, frankly, the fact he did not keep up with developments in the literary world.”

But what we now see as a rejection of the new is in truth more akin to a survival instinct. Roth showed an initial enthusiasm for Russian Bolshevism, because he saw in it (optimistically, if perversely) a chance for the Ostjuden to finally shake off the *difference* that he believed had made their persecution all too easy.

Western modernism could not offer anything but suffering for Jews. It represented a sharp, keen and divisive vision for a people who could only survive, Roth believed in vagueness - that vagueness including the whims of a benefactor such as the emperor (who had declared Roth’s own, Jewish-populated hometown his very own Jerusalem).

He yearned to be European, which meant for him sophisticated, learned and catholic (in every sense). For him, the France of the interwar years was the apotheosis of this ideal, while Nazi Germany was the nadir.

Nationalism, anger, mechanisation and godlessness had all combined into a soulless entity that had no hesitation in destroying a man merely because it could. In Rebellion, an early novel, Roth describes how a man whose entire way of life is based in the old world - treating heavenly and secular authority in the same manner, is destroyed by a system that essentially does so because its own grim internal logic deems it must.

After the invalid organ grinder Andreas has a minor altercation with an upper class bully on a tram, he is arrested and then released, to his relief. But, Roth writes: “If Andreas had known anything of jurisprudence, he would have known that the courts were already busy with his case. His was one of the so-called “express cases”, which, following a decree from the progressive minister of justice, were picked up and dealt with right away. The great grinding wheels of the State were already getting to grips with citizen Andreas Pum, and, before he even realised it, he was being slowly and comprehensively crushed.”

In an article for German exile paper Die Zukunft written in 1938, republished in Pushkin Press’s collection The End Of The World, Roth puts forward a monologue by a Parisian cab driver, who, conveniently, vocalises his own world view. As the bar flies fret over the coming war, Roth’s cabbie pronounces, “Don’t talk to me about politics! I know why the world is cursed, because I used to be a coachman. It’s conscience, gentlemen, conscience has been killed off. Authorisation has taken its place.”

Authorisation, for Roth, is the tool of the tyrant: in a foretelling of the Nuremberg “following orders” defence, Roth’s driver goes on: “when a customs official at the border hails out a blind or crippled passenger and subjects him to a search in his official hut, he reveals not a crumb of conscience. He not only has his authorisation, he has his empowerment [...] Authorisation kills conscience.”

“My horses had a conscience: my car has authorisation”, says the driver, lamenting the fact that while horses might instinctively stop to avoid running over a pedestrian, a car merely takes the instructions of the driver.

This scepticism, bordering on horror, of the machine age, is echoed by the Radetzky March’s Count Chojnicki. In a pivotal scene in the book, Chojnicki explains to the bureaucrat Trotta and his dissolute officer son how the age of the empire is about to be replaced by the age of the machine: “In Franz Joseph’s palace they still often burn candles. Do you understand? Nitroglycerine and electricity will be the death of us”, he pleads.

This, for Roth, is where things fall apart. It seems simple now to explain the horror at the modern world as a result of the first world war (in which Roth, while he did serve as a soldier in the Austrian army, massively exaggerated his combat role), but Roth’s backward glances were always about the future. The first author to mention Hitler in fiction, as early as 1922, he had, in spite of his ambivalence about his own background, which often drifted into the most basic tropes of European antisemitism (greedy Berlin Jews ripping him off was a worryingly frequent motif in his letters) a keen personal sense of what was good for the Jews.

He was, from the very earliest days, scathing of any accommodation with the Nazis. While other Jewish writers and intellectuals, including the incredibly commercially successful Zweig, sought to get by in a regime that despised them in the hope of keeping their livelihoods and lives, Roth found the idea distasteful and, essentially, impossible. He would have felt closer to the victims of Tsarist pogroms, and understood immediately the eliminationist instinct of the Nazis.

Zionism though, also seemed unpalatable. A school friend, Abraham Pares, describes inviting Roth to join the pupils’ Zionist society - essentially a social club for the Jewish contingent in the school. Roth’s apparently indignant answer was that he was “for assimilation... with Austria”. This dismissal of Zionism was a constant in his short life. Writing in 1929, in the wake of a massacre of Jews in Hebron, Roth argued that by pursuing the modern idea of the nation state, which had so recently torn Europe apart, Zionist Jews were “aping the recently failed European ideologies”. Roth believed that diasporic existence was essential to Judaism. “In seeking a ‘homeland’ of their own,” he wrote, “they are rebelling against their deeper nature.”

The “their” is telling, perhaps: Roth always feels, in his published writing at least, at one remove, observing. This is seen in how he wrote: He claimed to dislike locking himself away to write (thought would do it when a book deadline loomed) and instead preferred to set up in a cafe, and write between drinks and conversations with callers.

Alcohol and its effects loom heavily in Roth’s work. Roth is particularly interested in how it works not so much as a leveller, but as a flattener. In Radetzky March, and in the later novel Weights and Measures, the descent into alcoholism by agents of the emperor - soldiers or civil servants - is analogous to the decline of the Habsburg dream itself. Cast adrift, protagonists drown in slivovitz.

Roth himself was a prodigious drinker, and the correspondence referenced by Pim is frequently peppered with the self-pity, anger and remorse of the drunk. He lashes out and pleads within the same letters, the ever-patient Zweig being frequently the target of his rage and his projected guilt.

The impression, with or without alcohol (though in truth he is impossible to imagine sober) is of a difficult friend, and an impossible lover. His marriage in 1922 to Friedl Reichler, the young and beautiful daughter of a good Viennese Jewish family, must have felt like quite an attainment for the jobbing writer from the east. But his peripatetic lifestyle - Roth lived in hotels most of his life - and Friedl’s fragile mental health were a bad mix. By 1929, Friedl had suffered what seems to have been a complete mental breakdown, and was committed to an asylum. She would remain in institutions until she was murdered by the Nazis in 1940, twice cursed in their eyes as a Jew and a lunatic.

Roth himself died in 1939. Zweig, his dearest friend, committed suicide along with his wife Lotte in 1942 in Brazil, despairing at seemed the end of European civilisation.

In a recent essay in the New York Review of Books, Pankaj Mishra suggested that Roth, at least, died of natural causes. But one cannot escape the idea, reading the accounts of his alcoholism set out by Pim, that the novelist set out to drink himself to death. While Roth mocked Freud as “the father-confessor of the beautiful Jewish women of Vienna”, and would in an argument with Zweig quote Karl Kraus’s belief that psychoanalysis is “the art of living on one patient for a whole year there is an unmistakable death drive running through his biography, and indeed many of his characters.

But what characters! Hapless souls subject to the whims of history, governments and God (it takes chutzpah to call your novel about a long-suffering devout Jew “Job”, as Roth did); They are rarely at the centre of things, but fringe, forgotten, sad figures who can feel their world collapsing but have no idea how to halt the decline - instead they tend to join in. The Trottas, the family at the heart of the Radetzky march, carry a generational trajectory that matches Austro Hungary’s own decline; from bravado, to decadence to dissolution. They are born nostalgic, already aware that the structure that sustains them - the crown, the state, religion, is collapsing. Sometimes there will be a miracle, but these do not alter the trajectory of the world, even if occasionally they can lift an individual.

To read Roth now is to feel that same weight of inevitability: his native Ukraine is being punished for looking west, to European integration, as he did so longingly, by the forces of chauvinistic nationalism. Jews the world over once again feel that their existence - even in the Jewish state which Roth disdained the very idea of - is under threat. Palestinians are being the brunt of mechanised war, with the emphasis on what is allowed, rather than what is right.

As Roth wrote in 1938: “The ink has been shed in vain like the blood. We find ourselves facing the fact that the world for which we had once thought to write has become deaf and dumb, and we don’t have much of anything, perhaps nothing of all to seek there.”

Endless Flight is published by Granta

Wandering Jew - The Search for Joseph Roth is published by Notting Hill Editions